Amsterdam’s transportation network blends various modes of transportation across small geographic areas; different modes are usually given different ranks (Utne, 2006). There is even a specific Dutch word, woonerf, which means “living street.” Woonerf describes the concept of deferring private vehicle needs to those needs of pedestrians, bicyclists, and transit users; the lack of traffic signals in a woonerf forces commuters to “make eye contact and negotiate their passage” (Utne, 2006).

The approaches to private vehicle costs are also markedly different in Curitiba, Amsterdam and the DC area. For example, Brazil, The Netherlands, and the United States had diverse average gasoline prices; the prices for super, or high octane, gasoline in the countries were 84 cents per Litre, 162 cents per Litre, and 54 cents per Litre, respectively, in late 2004 (Metschies, 2004).

Gasoline in Brazil is approximately one and a half times more expensive than gasoline in the

United States; in The Netherlands, gasoline is priced at three times the value of gasoline in the United States. However, Curitiba’s gasoline use per capita is 30% less than that of eight comparable Brazilian cities due to its extensive, popular bus system (Birk, 1993).

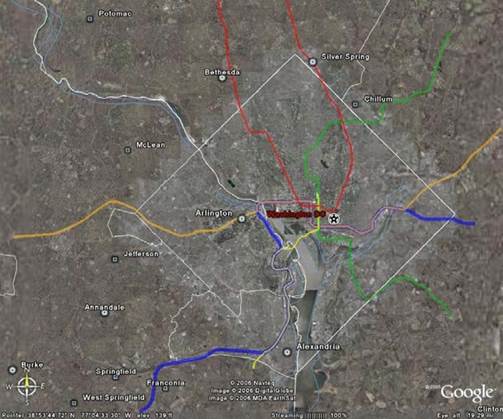

Why are private vehicles so popular in the Washington, DC region? The Metro rail system in DC has recently celebrated its 30th anniversary, but at its inception in Washington, “rail was far from the obvious solution to guiding the region’s development” (Schrag, 2006). The road building trends of the 1950s were still persisting decades later. Yet, a group of vocal citizen activists protested these road building trends and thus helped divert money back towards a rail network now known as Metro (Schrag, 2006). Some regional county boards, such as those in Arlington and Bethesda, at that time were “particularly farsighted” and shaped their communities via development along the Metro lines (Schrag, 2006). However, a lack of rail maintenance and improvements to the system in recent decades may explain the predominant transport mode for the region. Specifically, a lack of regional funding for any Metro improvements allows private cars to dominate the Washington, DC landscape (Sun, 2006). This domination by cars occurs despite the fact that the DC area’s Metro system stretches outside the city’s borders and past its 75 miles of highways; this is visible in Figure 10 (Google Earth, 2006).

Figure 10. Washington, DC borders and highlighted Metro lines (Google Earth, 2006).

Metro in Washington, DC is “the only major transit system without a steady source of funding” (Sun, 2006). For example, while roughly 10,000 Prince William County residents use Metro’s rails on an average weekday, the County pays no subsidies for Metro track maintenance and improvements. Without funding support from a high-level of government, Metro is in a precarious position. Based on ridership, an annual subsidy for Prince William County would reach approximately $5 million, an amount of money that could help the Metro rails significantly (Sun, 2006).

Ultimately, nations must use available research and technology to structure a sustainable transportation network that fits their cities’ requirements. As an example, Jaime Lerner, the mayor of Curitiba who was responsible for the original Master Plan, tailored the transport solution to address the city’s unique problems. He and his planners devised this alternate transportation system focused on buses; this did not simply replicate those in the West (Brown,

2001). While Curitiba’s population doubled since 1974, the automotive congestion declined by 30 percent (Brown, 2001). This success story demonstrates a fruitful investment in the city’s economic, social, and ecological well-being.

Уважаемый посетитель!

Чтобы распечатать файл, скачайте его (в формате Word).

Ссылка на скачивание - внизу страницы.